|

Hello readers and welcome to the fifth part of an ongoing series. It is my earnest attempt to document the process of composing a novel in the hopes that it may inspire others to do the same. While I think this series will be interesting to all readers, be aware that it is going to get pretty in depth into the writing process. (I also hope to gain further insight into how I come up with this stuff.)

(Note: Parts One, Two, and Four have followed my speculative dystopian manuscript Spheres of Influence. The epic Part Three covered my [stalled] office satire, Observe and Detach.) Feedback. This is an important part of the process that I had to force myself to do. After I sent the initial (shitty) first draft of Spheres to my editor Libby, one of her best pieces of advice was to find #beta readers to look through it. These would be people who might read similar books to what you’re producing and would have enough time to read a chapter of yours. And here’s the first bit of this advice: don’t ask too much of them. At this point I have been lucky enough to have a revolving cast of #beta readers, and while some have not been in full communication I am still confident they will get to it when they have time. My old college roommate Aric (he was the basis for a character in my *shameless plug* second novel Last Man on Campus) were willing to take a massive dive into each chapter and offer revisions. Try to widen your array of feedback partners so that you have a diverse skill set and readership type. I asked Aric a few questions about the SciFi genre, and that got him pushing me to consider this work more of a speculative dystopian thriller. I continued giving him chapters and he sent me even better feedback on the flow but also on the various themes, and some basic spelling and grammar I missed. If you can find a good #beta reader to have such back and forth discussions, hang onto them! My favorite piece of feedback from him so far: “...this is just so similar to what is happening that you can't put it down once you start.” Another #beta reader was Allan, a colleague from my old neighborhood board. He happened to be in a major city where a major event I riff on took place, and had some good real-world experience. Allan also urged me to call this a more “dystopian” book, and had some great thoughts on the initial themes. He also had thoughtful feedback on a specific piece of dialogue (again based on his own real experience) that worked so much better after I included his notes. This was another part of his response: “I don't really see this as science fiction since it's not that far in the future and warfare seems pretty conventional. I'd maybe call it a dystopian novel of what could happen if we continue down our current path.” I also want to shout-out my other #betas whose reading and feedback were important. Thanks to Josh for having many, many (many) rambling conversations over coffee about it first, and then being willing to read the first chapter as a reader. Thanks to Christie for even more conversations, but also getting started on her own work (and for giving me the chance to read it). Thanks to Karen, who has also read my first two books. Special thanks to Martin, who like my editor Libby also pored over an early (shitty) draft of this and gave me some great early feedback. I’m sure I am leaving out others who have conversed with me on this project, but that’s in favor of keeping your group wide. Back to Libby for a moment. This is another in a long line of advice that she has given me for years, but I was too ignorant to take it. I’m not going to claim I’m nailing it very well now, but I do understand why she implored me to have others read this manuscript. This is just another reason why she’s so good at what she does. So when should you start giving others a chance to look at your work? That’s a question only you can answer, but again I must stress once you decide it cast as wide a net as possible. If you can get feedback from readers and friends, you will go a long way toward formatting your manuscript in a way that it can gain larger interest. I now have some good ideas to put in my query letter when I get ready to pitch this to an agent. To that end, this post in the “How to Write a Book” series may be the last one for a while. It has always been about the process, but now that I am embarking on finding representation and publication I hope to document that as well. I hope you will continue to join me on this journey. Thanks for being readers.

0 Comments

Hello readers and welcome to the third in a series on this here blog I’ve been struggling with for years: shorter pieces focusing on the writing life and its challenges, daily affairs, and all it entails. That was initially what this blog was going to be all about, but it sort of got hijacked by the reading list and my “how to write a book” project. The first essay is here and the second is here if you missed them. And without further ado, here is the third installment in the Writing Life.

Listening to editors. This is another general piece of advice I have written about before but also struggled with, and I thought it was a great subject to talk about as writers are only as good as their editors. I have come to understand this through the Reading List since many of the books I had issues with could have used stronger editing. So how do we writers make ourselves listen to those voices who tell us things about our writing we may not want to hear? I reached out to one of my editors Anne Nerison of Inkstand Editorial (you may remember her excellent input from my “How to Write a Book” series) about this very situation. Here was some of her response: “While you as the writer know your story inside and out, there is something to be said for coming at a story from an outside perspective. This fresh set of eyes can help catch issues that you may not be able to see, simply from being too close to it..” I thought this hits the nail pretty much on the head, and helps point to what we need to think about as we work on our drafts. For however many versions of it you may go over, you’re still just seeing it with your own eyes, and your own imaginative voice. It’s not until those same words get pored over by a professional who does this for a living can they truly measure up and be ensured to flow. And I have to stress: if you find a good editor, hang onto them and listen to them! A good editor will be up front with you about whether or not to take their advice, how much to listen, and other details that form the basis of the relationship. This insight from Anne was also worth thinking about: “An editor's loyalty is to the manuscript in front of them, which means we want it to be a strong piece of writing. Our advice, then, is to aid in that goal.” It’s important not to think of your editor as being in an opposition role; rather, they are here to help guide your book or story into a better shape. There will be plenty of other voices out there looking to tear down your work. Stick with those who give you feedback that actually improves your writing. I know it can be difficult when we have such singular visions about our work. But the more you learn to form a collaborative relationship with your editor, the easier it becomes to see your writing from another perspective. Because that is a lot of what listening is: having the empathy to open up and see things from another’s viewpoint, a not-to-easy task in today’s oversaturated world of infotainment. So listen to others, but especially your editor. If they are doing their job, yours should be made that much easier. Hello and welcome to this installment of the 2018 Reading List. Last time we explored the world of Mrs. Dalloway, and now I am turning toward an author I have long known but never read: Don DeLillo and his masterpiece 1985 novel White Noise.

As with Virginia Woolf’s excellent prose, this too was one of the best books I have ever read. It feels like this novel has seeped into the national consciousness since its publication over thirty years ago, but reading it in the age of social media it still felt incredibly relevant. The advent of technology, eco-disasters, family disorder, academic redundancy; all of these themes have not eluded American life and in fact I have seen many of them get much worse in my lifetime. I won’t delve into the plot (such as it is) in the hopes that this will inspire others to read this book, and will dive straight into a few lessons writers can extricate from this work. Use of thematic elements. This alone could be the source of an entire essay, and thankfully the edition I had of the book did include quite a few of them to help me gather my thoughts. While I would say the obvious themes of the book are in plain sight (the “airborne toxic event,” “Dylar”) the way DeLillo presents them in the prose is brilliant. What first starts as television ad jingles interspersed throughout the Gladney home slowly becomes part of the text itself, and seem to literally be running through the mind of the protagonist by the end (“Visa, MasterCard, American Express”). But this is just one theme - I would argue the largest is death and how much it looms over the American consciousness. The protagonist’s wife searches (and debases herself) for a pill that will cure death, and by the end Gladney himself is convinced of a much darker way to prolong his life. Writers can attend a master class in how to approach thematic elements in literally every page of this novel. Using the novel to show society. This is arguably the novel’s largest success, as DeLillo uses his characters’ perspectives to show the consumerism obsessed populace of the early Eighties. The supermarket becomes a religious experience, academic life has become a series of intricately developed specialities (“Department of Hitler Studies”), and we are assailed all around by toxins and other elements that are slowly killing us. I had to set it aside and ponder the relations to our current malaise at many junctures. (This book is also the first since Catch-22 to make me laugh out loud multiple times.) Use of voice. This struck me in the sense that Jack Gladney is essentially DeLillo’s voice, and yet it is not. Gladney views the world through academic suspicion, and yet is swayed by another academic (Murray) into committing a horrific act of violence he supposes will set him free. All throughout the book we encounter Gladney’s personal experiences of the world, viewed through a more jaded author’s handiwork, to amazing effect. Writers looking to hone their voice can find few better works of such phenomenal example. Again, these are but three lessons for writers in this monumental book, and I would encourage anyone who has not picked this one up to do so if you can. It’s that incredible of a novel, and is so well-written that each passage has miles of depths to explore critically. And I would welcome any comments from those who have read it as well. Up next, I needed a bit of a breather, as White Noise hit me hard on several levels. Therefore I’m veering back into (British) commercial fiction and returning to an author I have not read in years - Nick Hornby and his first novel High Fidelity. I also plan on reading more female authors later in the year, and am always open to more suggestions on that front. As always, thanks for reading and writing. Hello and welcome to the second part of a new, ongoing series! It is my earnest attempt to document my own process of composing a new novel in the hopes that it may inspire others to do the same. While I think this series will be interesting to all readers, be aware that it is going to get pretty in depth in the writing process. (I also hope to gain further insight into my process and how I come up with this stuff.)

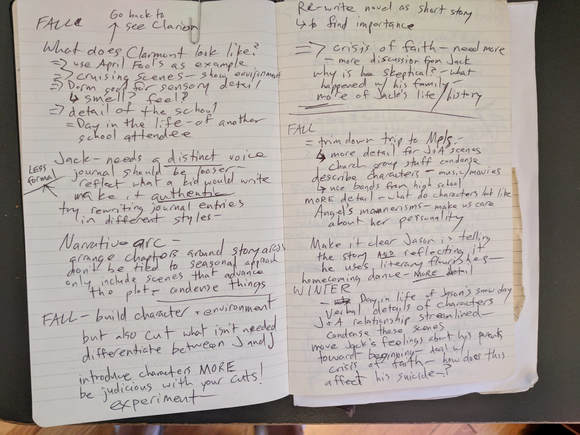

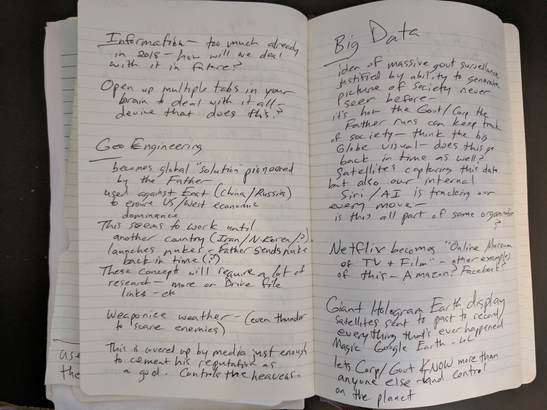

Part One (Ideas and Outline) is here if you missed it. Drafting. So you’ve got a killer idea for a book and you want to start seeing it as you envision? This is the point when you put words down on paper (or on the screen) and consider if they connect. As I stated last time, the idea process can take years, but you’ll know when you have reached the point of wanting out outline it. Once you have the narrative set out, an idea of the characters, settings, and other details, you can make your first attempt at writing it. A point here about shitty first drafts, which readers may remember comes from Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird. As I tried to surmise back then, Lamott is basically saying that everything we writers churn out in the beginning is going to be (more or less) crap. This is alright, since we are just finding out what we mean to say with each project. Whatever sits in front of you has many, many rewrites to go before it should be seen by another person. Your editor will guide you through the later steps of this process (more on that next time), but overall it will always be up to you to decide who gets the first read. It might be your agent, or a friend you trust, or somebody random you’ve queried on the Twitter machine. But you need to ensure the draft is in its finest form, and that you are ready to take critiques on it. So how do you start? Again, for this series I’m mostly pulling from my current manuscript, of which I have finally been able to churn out close to 30,000 words. By the time I outlined Our Senior Year I had most of the story figured out. But it took a major read-through by my wife’s cousin to get me to see the story as it really flowed, and then how to make it better. My editor Libby shephereded me through the story process with Last Man on Campus, and I don’t want to shine a light on her until I can do it with an entire post. And the book I am slowly walking toward agent queries (Observe and Detach) is in the throes of another massive rewrite/re-envision, and will be the focus of the next post. In the case of my current manuscript, which as yet has no title, the major ideas had been percolating in my brain for several years before I finally sat down to outline it this year. While this was not a conventional outline (in narrative terms anyway), it helped guide me toward telling the story as I saw it. I made some last-minute decisions (adding a third character as a sort of narrator within the tale) but made myself sit and crank out at least 2,000 words each session until the end of February. While I’m not comfortable yet revealing the two major characters I am somewhat ambivalent about this character, an underground journalist/historian. And it should be noted that this is not actually the “shitty first draft” of this book, as even I am too timid to put that on the internet (it has graced the eyeballs of a few friends the past few months). But without further ado, the first two(-ish) pages of the second draft: ---- Things have changed since two thousand aught one. The year them towers came down. Some people say that’s when things went to shit in this country. I always used to tell them it was way before that. And President Trump? Saw that coming a mile away. This country has been ripe for demagoguery ever since the first Kennedy clone got blown away. You know the government cloned him, right? That was Leonard. Lenny to his friends. One of the last interviews I was able to get, before the time of Samson. Before things really changed in this nation. But I’m already ahead of myself. I was able to collect interviews from North American Sphere citizens right up until the point of (Lord) Samson’s full ascension to the Internet. After that he controlled pretty much all that went on there, darknet and light, so I was forced to move my research underground. Back to the paper movement, and all that. Yeah, it is a real thing. It had to become one. I printed out a bunch of the interviews before sending them to the exclusive garbage can in the networked sky, and Leonard is one of the last. See, people still believed in weird ass shit before Samson. Before people couldn’t think for themselves enough to realize the con was on them, God wasn’t on their side and half the country got turned into a wasteland. But again, ahead of myself. Leonard saw what some would say was the truth inside of the truth. And from my current position, I can fully say that the government successfully assassinated Kennedy the man, not the clone. In fact, clones did not exist up until the 1990’s, and would you believe the government tried outlawing the practice in these here (former) United States? I know, what a waste. Things look different the more you get past them. But he wasn’t wrong to place the situation somewhere around when those towers fell. Conspiracy theorists were rife back then, hell you shoulda seen some of the theories. Didn’t help that their own government seemed to be blowing up buildings alongside those the terrorists hit. Controlled demolition, Leonard might have spat. And all that. You see, for a long while the people of this country thought they controlled the government. Thought they had some say in the corporations running rampant over their lives, in who the people with the most money got to buy and sell for public office. A lot of this changed in the Trump era, of course. But he just took advantage of what really happened in the populace after the attack. The change in the society. See, up until then we were ready to take down the government at every stage. People ran for the government pledging to get rid of the government. That’s how gung-ho people were about this shit, I can read interviews to prove it. But I won’t, cuz it’s a waste of everyone’s time. But after the attacks, suddenly they were ready to let the government do whatever it wanted in response. So the Patriot Act gets signed into law in less than a month. The NSA is allowed unlimited collection of our data. Multiple illegal wars spun out of control all across the Middle East. Calamitous events throughout the world, violent events, and while the scramble to do something about it is intense, there is next to no action on the real problem of climate change. We were so eager to let the government spy on us and pretend to protect us that we didn’t see the forest before it burned down. Trump exploited it like any true huckster; Samson perfected the technique. People were damn near ready to believe anything in the “post-truth” era. Not all of them, of course, but like the old adage says, “you can fool some of the people most of the time.” It all really began with the weather patterns. Subtle at first, pretty bad by the quarter-century mark, untenable in the time of Samson. People were ready to believe in somebody who could make it all go away, tell them a story they wanted to hear. That was a big part of Samson’s success: the storytelling. So Trump comes along, and bamboozles his way through an entire Presidential term. Yeah, I still can’t believe I have to write that. People remember him in the interviews. Mostly what a shit person he was. As if he wasn’t that way his whole life. They had a funny way of not remembering that, a lot of subjects. So then we had the populism turn in the United States. Boy, were intellectuals like me happy when this happened. People, marching in the streets in support of science! Actual policy proposals getting through a newly turned Democratic Congress and enacted in the hopes of reigning emissions. Funny thing about those emissions, though. They really needed to stop happening right around the time Trump descended that escalator in 2015. He of course famously tweeted climate change was a “hoax” and therefore installed nothing but rapacious capitalists in places of high influence in his administration, ensuring that it would be too late forever by the time reasonable persons got in charge again. This wasn’t understood by people until it was too late. It was somewhere in the second term of that once-ever Socialist President of the (former) United States. I mean, we thought the near-destruction of New York City by hurricane Sandy would have done it. Or the utter devastation wrought by hurricane Harvey in Texas and Puerto Rico. But no, it had to be more than that. We had to lose Florida. Oh it’s still there, of course. Most of it. But forget that lifetime altering goal of beachfront property. It seems what wasn’t understood was that with the changing patterns in the ocean, all it took was a massive storm to do what scientists predicted would take place over a century. So thousands of people had to die because of it. There was a reaction to that, all right. The first million-plus protest against Washington DC about the inaction taken. Why couldn’t we just build a huge wall out there in the ocean or something? Ok, most people still didn’t really get what was happening. That unfortunately would not change much in the future. Remember those documents that came out in the beginning of the century? The ones that proved Exxonmobil had been engaged in a pattern of cover-up and deceit regarding the true outcomes of their very own climate studies? All in the name of continuing massive profits? The same thing kinda happened to the US government. Except it was kinda much more worse and horrible. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I won’t go on much more as each of you will have your own individual tale and will know how to tell it once you maneuver through these steps. But I definitely welcome any thoughts or criticisms, as that’s what this part is all about. What worked for you? What didn’t? Feel free to email or write something in the comments. And let me know how your own writing process is going. This gig is meant to be collaborative, and I need to be better about thinking that way. In Part 3, I will be taking a deep dive into the editing process with my third novel, and hope to be able to explain coherently the importance of a good editor who is unafraid to tell you when your writing, for lack of a better term, sucks. I also hope to do a parallel series on what writers are for, and attempt some more personal essays as the year progresses. Thanks for reading (and writing)! Hello and welcome to the first part of a new, ongoing series! It is my earnest attempt to document my own process of composing a new novel in the hopes that it may inspire others to do the same. While I think this series will be interesting to all readers, be aware that it is going to get pretty in depth in the writing process. (I also hope to gain further insight into my process and how I come up with this stuff.) The idea. First of all, you need to have the idea for the book. This can literally be anything. Look around your life. What do you see? Injustice? Hilarity? Torment? Wonder? Characters? Setting? These can all be a starting point. Obviously I can’t tell you how to come up with your own ideas, but I can offer a few guidelines that have worked for me. The most important point: don’t stress about it, the ideas will come. I wish I could offer a simple timeline of when my ideas hit me, but the truth is I never knew when I would have enough to create a book. True, the first two novels (as I’ve stated elsewhere) I carried with me for years before I committed them to paper. And that’s not a bad way to start - if you have something you think should turn into a proper book, then you are ready for the next step. But for those of you who aren’t there yet, don’t fret; it will come. The next point: what do you bring to the table? How do you see the world differently from others? What kind of “hot take” (to use an awful current expression in the journo world) do you have on an important issue that you could translate into a fictional universe? I can only illustrate this with my own work, so here goes. My fourth novel is going to be a dystopian tale set around the year 2050, and features a major struggle concerning humanity and its existence in the age of climate disruption and geoengineering. Obviously I didn’t come up with all of that at the same time (but that would have been awesome). I was very much influenced in a few essays I read over the past four years - this one in The Point about genetic manipulation, this one in the NYRB about geoengineering, and this one (big time) in the LARB about the writer Amitav Ghosh and his request for stories about the largest issue of our time. But of course the list of influences is never ending - the 2013 Spike Jonze film Her radically altered my perspective of where Artificial Intelligence was heading, and the 2015 film Ex Machina made me terrified of a similar notion. Books such as Gibson’s Neuromancer showed me how to craft a compelling, futuristic narrative. That’s the great thing about prompts like these - each writer can take away their own message. The major lesson to draw from all of this is to overload your circuits with what you follow the most, and eventually, if there is a story there, you’ll find it. I had to percolate this novel idea for years, in random locations, pondering over what it was going to be. Then I created a Google Doc where I kept all my notes and considerations, links to those pieces so I could re-read them, and even some beginning drafts. You can do the same in a simple notebook. The important part is getting it down. The outline. Once you have the idea, and its solid, you can move on to the outline. Here is where my advice is going to be a little more tailored, and it may not fit your book at all. Essentially an outline is the plot, characters, and themes all put together in some kind of coherent fashion that you understand enough to refer back to when you need it. Again, all I can do here is explain my own process in the hope that it is helpful. For Our Senior Year, I literally broke the entire story down into its seasonal parts, in different ways. I’m attaching a picture of my notebook from that time to give an idea - Last Man on Campus was a pretty similar operation, in which I had the basic idea of the story broken down into the two semesters, and then had to work backward as I was writing to fill in some of the mythology of the society running the show (*spoiler*). Both of the outlines were basic - start with a major plot point, how it shows your characters, and their reactions. Et cetera. I won’t even delve into the insane process I followed for my current manuscript (Observe and Detach) as the story has evolved quite a bit in two years and I’m not too keen on showing where some of it comes from just yet. And unfortunately novel #4 is not following these outline steps at all, which I must stress is perfectly all right. In lieu of creating much of an outline as of yet, I sat down and cranked out what I think are going to be the major themes of the book - After almost four years of thinking about this, I have just enough story and character to begin the first drafts, and to be honest I have no idea where they are going to take me. There will be a lot more grist on this topic (Drafts) in the next post, so all I will say here is to not worry about how dense (or not) your outline of the novel is - if it contains the major characters/plot/themes that you want to get on the page, you’re getting there. Thankfully the wonderful technology of the notebook allows for you to always add more stuff - mine is crammed with papers and clippings but I still go back to it when I’m preparing a book. These are the techniques that have worked for me in getting a book through its initial stages. Short stories or essays (or really anything that’s not a novel) are different beasts, and if/when I ever get better at those forms I’ll try my hand at explaining how to come up with them. Next up will be the initial (as Anne Lamott would say “shitty first”) draft. I hope to get a post about that process up by the end of this month, again following my own process and how I’ve done it in the past. I also plan on sending my current manuscript of Observe to my editor by then, and may write a little something about that as well. Feel free to send any and all questions and comments my way, through email or in the comments. I want to hear about your own projects, if my advice is helpful, and how you come up with your own ideas and outlines I will also have an essay on the first book of the 2018 Reading List (The Handmaid’s Tale) up by the end of the month. Thanks for reading! My first novel was published by North Star Press nearly three years ago. 2014 seems like a long time ago: Obama was still POTUS, and nobody even considered the upcoming election much yet. I was preoccupied with a lot that year, including getting the book, Our Senior Year, finished and the cover ready to go for my events. For those of you who haven’t read it, the book is essentially a fictionalized account of my time at a small high school in Iowa. I named the town Clarmont, a pastiche combining another nearby town, and patched together a few of my best friends at the time as characters. I also split my personality in half and had them be best friends, a decision I’m not quite sure worked very well but was useful in telling the story from two different (albeit similar) perspectives.

I’d recently read Bram Stoker’s Dracula, one of the first “horror” novels (depending on your time frame) of the modern era, and one told entirely through epistolary forms of the time: monographs recorded for others to listen, letters, and diary entries. This got me considering a journal entry to tell one character’s side of the story. This journal is located by the other main character at the beginning of the tale, and he uses it to tell the story in what ends up being the actual book. There are some plot twists based on my experience at that town over four years, including an amalgamation of some car wrecks, and a suicide. The friends were based on people I got to know quite well during my senior year there, as I had run with a different group of people aimlessly (and neurotically, though I wasn’t aware at the time) up to that point. I realized the people in my own grade were having an awesome time, and that it was time to start seeing what they were into. I have since come to understand our activities as pretty stupid, but no too much outside the norm for kids of any era. But all of this did not bode well with my parents, who raised me on a farm outside the town based on pretty strict religious structure. This is reflected in the character’s attending a youth group night at a local church. This entire novel was really a reaction against my upbringing. Circa 2013, when I was finishing the last drafts, I was coming off an important conversation with my parents a year earlier regarding my breaking away from their Christian faith. I would end up telling them parts of what the story would entail, and tried to make sure they were aware that the parent characters are not really them. One is an alcoholic, and my father doesn’t touch the stuff, and my mother was not overbearing and mean like in the novel. Still, I had conceived the novel in my high school days as being against this type of strict upbringing. Yet I couldn’t view this work through any other lens than a strictly religious conflict up until now. I’ve recently had some powerful emotional breakthroughs regarding all of it (the ignorance coupled with the extreme fundamentalism) and have come to some much better ground surrounding it. I’m not so angry any longer, and it feels better. I thought it would be as good a time as any to revisit what was driving this first novel. A lot of it was driven by anger, and fear. Since our initial discussion I had since come to see how I was raised through a mostly negative light, and struggled to distance myself from it through this novel. There is a discussion in the book dealing with a documentary I watched in real life produced by PBS describing a lot of the fallacies in where the Bible comes from. After, the father and son discuss why they don’t believe in this stuff anymore, but must for the sake of their mother. This was one of my first clumsy attempts at inserting commentary I’d arrived at much later into a fictional time zone where part of me existed. I was also at the time afraid my parents would know more about what I thought. I thought this passage in the novel would be enough to cover some of this. It never was. But that’s another great revelation to hit as a writer: I’m not who I thought I was. That’s right, I can evolve, both through life and in my work. My marriage has taught me a lot about the life part, now it’s time to tackle the writing bit. The person who finally finished that book in 2013-14 is not the person sitting here writing this today. I have a new, and different outlook on religion and all of its various manifestations through society. And instead of forgetting about it, like it’s not a part of me, I have come to the conclusion that I can only incorporate it into my writing. I have seen so much of it used in the wrong way, in ways that will affect me for the rest of my life. But instead of the anger, I have to approach it with the opposite. Compassion, understanding, but also ruthless interrogation. What causes humans to believe such things? Where does it come from, and where is it going? I have no idea, and things are only getting more confused with the technological revolution of recent years. AI appears to be the closest thing we might get to a “god” on this planet, so what does that mean for religion? These are all things I didn’t realize I wanted to write about until they wouldn’t go away and kept turning into a huge idea. Therefore, I am going to begin drafting a new book, involving ideas about the future, climate change, technology, and seeing where it leads. I’m also going to continue re-writing Observe and Detach so it’s ready for an agent, but I can’t suppress this any longer. It’s time to start harnessing the tide of creative growth that comes from a healthy examination of one’s path. That’s my main point for you aspiring writers out there. Look at where you come from, gaze at what you wrote, but don’t let it define you. You are never who you thought you were. I wish there was some other better way to figure this out besides time travel or something. But as I near the midpoint of my thirties, I’ve come to understand that if you can learn from your mistakes, and where you come from, you’ll go a long way toward finding out where you’re going. (Also when I first started thinking about this essay, I couldn’t help get this infamous YouTube video out of my head. Denny Green was a perennial character in my parent's’ living room as head coach of the Minnesota Vikings a million years ago…) It is time once again for what will be the final update in my Year of Living (Actually Reading) Fiction. Those of you keeping score at home will recall I initially promised to read another two books this year. While I will be getting to those next year, I’ll also have more on the major lessons learned from this experiment in a post re-launching this experiment in January.

After taking on Faulkner’s legendary Sound and the Fury I took a decidedly different pivot in my next selection: Exodus by Leon Uris. Published in 1958, it is an epic novel about the creation of the state of Israel after World War II. Uris traveled thousands of miles throughout the Middle East interviewing people and researching places for the book, and this imbues it with a historical sense that engaged me through nearly 600 pages. There are many characters and the book spans half a century, but I will admit the writing is actually quite dry and does just enough to keep the narrative flowing. Here are two lessons I drew as a writer from this monumental work:

While I’m glad Uris was able to keep my interest in the tale, I would be hard-pressed to recommend this book to a contemporary audience. As I’ve already stated, the writing just isn’t that great, and Uris presents the story of the Jewish people in an extremely one-sided way. As just one glaring example, the Arab people making up the states surrounding Palestine are almost uniformly presented in a harsh light, being described as backward and even “dirty” people who only reached salvation through the Jewish farming methods being used in the deserts. While things like this absolutely did happen, anyone who studies history as I have ought to know that things are never as simple as people would like them to be. Especially given the context of recent events transpiring between the US and Israel, it is important to note that this is just one (fictional) version of events, and while the historical narrative is quite engaging, anyone who wishes to truly understand the history of this part of the world would do better starting with some non-fiction sources. So that’s it for my first experimental year of fiction! I’ll be back next year with a post running down everything I have gained from this experience. But for now I’ll say this year was incredibly revelatory for me. I gained some new favorite books and learned a ton from the masters of the written word that have gone before me. I hope I was able to distill some of this into useable knowledge for other writers out there. I would also highly recommend this type of experiment for anyone who wishes to hone their craft. Thanks to everyone who read my posts in this experiment throughout the year, and I’ll see you on the other side of 2017. I want to write today about an important facet of the writer’s life: being alone with your thoughts enough to compose something on the page. While some of you out there may be lucky enough to write by yourself or in a separate room, odds are most people have to deal with this situation simply by dint of having a relationship with another human being.

My wife and I lived in a very cramped apartment for the first five years of our marriage. This led to numerous issues regarding space, and while a lot of it got rectified when we moved a bigger place last year, we still could not avoid the fact that we are occupying much of the same area together, almost all of the time. How can we as writers learn to deal with such a situation? How can we with partners in our lives learn to be alone, together? First I’d like to address the simple matter of how to write even when there is somebody in the same area doing something completely different like watching television. Headphones can be invaluable to cut off the noise, and to place you in the right mindset for writing. For me that’s a heavy dose of classical and/or ambient music. But more to the point, we as writers need to find the proper mindset for working on our craft even in a fairly cramped environment. My wife has her own concept of “alone time,” which she needs just as much as me. Even in a one-bedroom apartment we find our ways of separating, whether that’s moving to the bedroom to read or putting on my headphones and jamming out on a story. While we do have to occupy the same space, we manage to live in our own worlds at certain times. I think this is an important concept for anyone who lives in close quarters with another human being: make sure they too have the space they need from you, when they need it. This can be tough to understand and acknowledge, but believe me, if you can find an arrangement that works out for the both of you, it will do wonders for the entire relationship. But I want to go deeper than that. What does it truly mean to be alone, together? We as writers are basically unable to do our jobs unless we can be solitary and cultivate our thoughts. How is this possible in our world full of distraction and people? Those who work with me have probably come to know me by turns inherently taciturn and, as I’ve been described by too many people to count, “quiet.” This was especially apparent in my previous job, in which personal connections broke down and I became utterly consumed with keeping to myself. While this led to some humorous anecdotes in my current manuscript concerning neurotic behaviour in the white-collar workplace, it did not lead to me connecting very well with my co-workers. I find myself currently employed in a bookstore, surrounded by some of my favorite works but also by people who do a lot more thinking before they speak (not a huge concern of the office-dweller, in general terms). And yet even here I find myself not speaking much more, often because I have a lot of ponderous thoughts about my books going on in my brain. While part of me keeps trying to make myself interact more with my fellow booksellers, many of whom are very deep people with interesting stories to tell, I must remind myself that the work is residing up there in my cranium, and to make sure I allow myself the time needed to grapple with it. Those of us who deign to use the written word to tell a story need not be so afraid of living a withdrawn life. I cannot stress enough how important it is to retain the singular lifestyle required of the writer in various circumstances. I am lucky enough to have a job in which that isn’t too difficult, but I would highly recommend this to any aspiring writer: find ways to keep within yourself and your thoughts as much as you can. That’s not to say you should be inwardly focused all the time, but you will never reach your full potential as a writer unless you can be alone with your thoughts. Whether that’s being home alone, together with your significant other or alone among others in your workplace, it’s imperative to cultivate that mindset as often as you can stand it. On this I can only offer my considerations as I ponder the direction of my writing career. While the first draft of my third novel resides on my hard drive, I have for the past few years been chewing over the direction of my fourth one, and how it can reflect reality. This began as the seed of an idea as I was waiting for the bus some afternoons after the office job, and continued into a bigger notion the more I was able to contemplate it, either when others were present or own my own. The important thing to note here is that I would not have been able to get this far without being able to honestly and deeply appraise my own thoughts. Make sure you are giving yourself the same amount of space. This ties in with what I hope will be my final essay on the writing process this year, which is a doozy: What exactly is a writer for? That is, what are we as purveyors of the written word attempting to do with our careers? I’ll be the first to admit I have expressed utter cluelessness on this score for a long time, but as this year has progressed I have come as close to an answer to that question as I’ve gotten yet. I hope to get that essay out of my brain before this horrendous year has passed. And of course, stay tuned to this space for the final few updates in my year-long experiment in reading fiction, the incredible results of which have guaranteed its continuation into the next year (more on that next month). Thanks for reading, and as always feel free to add your own reactions to these ideas in the comments. Happy holidays, everyone! It’s time once again for another update in my Year of Living (Actually Reading) Fictionally. To kick off the second-half of this experiment I began with Jane Smiley’s Pulitzer-winning 1991 novel A Thousand Acres, a rich narrative of life on the Iowa plains that takes place around the time I was born. This book hit me personally in a few ways that I will discuss later, but first I wanted to draw out the two major writing lessons I gained from this amazing novel.

I would highly recommend this novel for anyone who is looking for examples of how to write intricate descriptions and tell an amazing tale at the same time. But what really hit home for me with this book was the story. Essentially a modernization of Shakespeare’s King Lear, Smiley tells the story of a father with three daughters who decides to leave his farm to two of them, and the consequences of that weighty decision over the course of a farming season. Needless to say this does not go down easily, and causes the daughters to each remember and respond to their awful histories in various ways. This reminds me of what I also face in the future: the passing down of a stake in my own family’s farm in Iowa. Many were the months I spent working hard in the hog fields or in tractors during the harvest, and yet I must admit feeling ambivalent about the prospect of taking on that land when my parents’ generation passes. Another character named Jess returns to his family after spending years away in Canada to avoid fighting in Vietnam. When he gets back, he irritates the farmers that have been there for generation by speaking about organic farming and how much the chemicals used to kill weeds probably affected his friends’ abilities to have children. This character really resonated with me as I have struggled with these same issues. Things I took for granted as part of the family business (using Monsanto’s GMO seeds, spraying copious amounts of chemicals, etc) I now see as a principle reason for many of the food-related problems in the world. Coming to terms with this was no easier for Jess, who (*spoiler*) also does not stay to run his family’s farm. All of this being said, this book was a great start to the second-half of my fiction year. Next up I will be reading Chuck Palahniuk's Fight Club. And stay tuned to this space for more updates on my third novel and for some discussions on short stories and other topics. Thanks for reading! It’s time once again for another update in my year-long experiment of living (actually reading) fictionally. Except in this case after five fiction books in a row, I decided to tackle one book on the art of writing. More specifically, Francine Prose’s excellent Reading Like a Writer. Prose (whose name almost automatically makes her qualified to pen such a book) is the author of numerous novels herself, and this nonfiction work is an attempt by her to distill some of the knowledge about understanding fiction she has gained over the years. I found it to be a very helpful book, and one that will stick with me for some time. I would recommend this one for any of you out there who are trying to become a better writer because it certainly gave me a ton of new insights. I came away from this book with a new appreciation for many writers, including the Russian playwright and author Anton Chekhov, whom Prose uses in a final chapter to illustrate how a writer can attempt to become a completely dispassionate observer. While I’m not entirely convinced I can set aside my emotions in such an extreme manner, I definitely want to read more of this guy’s work.

As usual, I want to dive into a few major lessons on writing that I was able to take away from this book, but obviously this will be a bit different from the others.

There is a lot more to be said about this book that I am not going to cover here, but I would highly recommend it for anyone who loves reading and would like to become a writer themselves. I know it is going to assist me immensely as I tackle the second-half of my reading list for this experiment. (Prose also includes a hefty list of reading recommendations at the end of the book, many of which I hope to get to someday.) And speaking of my reading list for the second-half of the year...thanks to all of you for the excellent book suggestions! Unfortunately I was not able to include all of them for this year, but don’t fret; I am strongly considering pushing this experiment into next year, so much has it helped me as a writer thus far. I also hope to be able to pursue a few other experiments regarding short stories and some other stuff this year. But without further ado, here are the titles I will be tackling through December: A Thousand Acres - Jane Smiley Fight Club - Chuck Palahniuk The Sound and the Fury - William Faulkner Exodus - Leon Uris Neuromancer - William Gibson Bird by Bird - Anne Lamott Again, thank you very much for all the recommendations. I hope to be able to fit many more fiction books in my life over the next few years, and it helps to be connected to so many readers! I will return to this space shortly for my next essay, as well as branching out into the territory of the short story, continuing the path to publication, and offering more info on my next novel. Stay tuned, and as always, thanks for reading! |

AuthorJohn Abraham is a published author and freelance journalist who lives in the Twin Cities with his wife Mary and their cat. He is writing a speculative dystopian novel and is seeking representation and a publisher. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed